Home of the Infantry Regiments of Berkshire and Wiltshire

The 66th (Berkshire) Regiment 1756-1881

This section summarises the main events in the development of the Regiment from its foundation up to the time of its amalgamation in 1881. For further information see The Royal Berkshire Regiment by F Loraine Petre, 2 volumes, originally published 1925, reprinted by the Museum in 2004 and available from the online shop.

1756 Raising of 66th Regiment of Foot

A Grenadier of the 66th in 1768

The outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756 made it necessary to increase the size of the army and a number of regiments, amongst them the 19th Regiment (later to become the Green Howards), were ordered to raise second battalions. Two years later these battalions became regiments in their own right and were re-numbered accordingly, the second battalion of the 19th becoming the 66th Regiment of Foot. However, the 66th itself played no active part in the Seven Years' War. In 1763 the Regiment went to Ireland but the posting was short lived as the following year they went to Jamacia where they relieved the 49th Regiment (later the 1st Battalion). In Jamacia they were deployed on a number of times against what is desribed in the regimant history as 'rebellious negroes'. Further service followed in Ireland, Gibraltar, West Indies, Halifax, Jersey, Ceylon India, Nepal where the British were engaged in operations against the Ghurkhas, later to become staunch allies but at that time bitter enemies and finally St Helena where they joined the 2nd/66th.

In 1782 as part of the attempt to assist in recruiting the 66th received a county title and became known as the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment.

1803 The Peninsular War

Battle of Talavera 28 July 1809

In 1803 the 66th was ordered to raise a second battalion, the men coming from the newly formed Army of Reserve. The original intention had been that the new second battalion should remain as a permanent home based recruiting and drafting unit for the senior battalion. This system soon collapsed under the stress of war and in 1809 the 2nd/66th was ordered to active service in the Peninsular War under Wellington and gained the battle honours 'Douro', 'Talavera', 'Albuera', 'Vittoria', 'Pyrenees', 'Nivelle', 'Nive', 'Orthes' and 'Peninsula'. At Albuhera the 2nd/66th lost its Colours and was all but cut to pieces by the Polish cavalry, with only 52 men still standing when the unit was relieved.

1816 The Island of St Helena and the Emperor Napoleon

Funeral of Napoleon at St. Helena. The 66th Regiment was part of the colony garrison during his exile. Six grenadiers of the Regiment helped to carry his coffin to its tomb

In 1816 the 2nd/66th sailed for St Helena to guard Napoleon, who had been despatched there following his defeat at Waterloo. It was joined the following year by the 1st/66th and on 24 July 1817 the two Battalions were amalgamated. In September that year the officers of the 66th were received by Napoleon. When he died in 1821 it was grenadiers of the 20th and 66th Regiments who bore his body to the grave.

1822 Defending the Empire

A soldier of the 66th in winter, dressed to survive in the cold of Canada

After the death of Napoleon the 66th returned to England and for the next half century experienced the typical life of an infantry regiment serving at home and abroad. Postings included Ireland, Scotland, India, Gibraltar, the West Indies and lengthy stays in Canada (1827-40, 1851-54). Although despatched to India in 1857 the 66th arrived too late to take part in the suppression of the Indian Mutiny. However, it remained there until 1865. (For greater details of their sojourns in Canada and India try searching the Regimental timeline.)

1880 Battle of Maiwand

In 1870 the 66th Regiment was again sent to India. Early in 1880 it was ordered to Afghanistan, which the British had invaded in the previous year after the massacre of their envoy and his escort at Kabul.

In July information was received in Kandahar that the Ayub Khan was marching on the place with a force described officially as an advance guard of irregulars, and a brigade was at once sent out to intercept him. It was commanded by Brigadier-General Burrows and consisted of two Indian cavalry regiments, two Indian infantry regiments, a battery of Royal Horse Artillery, another of smoothbore guns, and six companies of the 66th Regiment, under Colonel Galbraith. The smoothbore guns had recently been recaptured from some mutineers and were manned by a hastily trained party of an officer and 42 men of the 66th.

On the morning of 27 July the cavalry advance guard reached Mahmudabad, on the arid plain of Maiwand, about 45 miles from Kandahar. The village stood on the edge of a deep, dry, watercourse and on the plain beyond it they saw the Afghans - not the small force they had led to expect but a great Army, streaming eastwards towards Kandahar. It was later established that the force consisted of 4,000 cavalry, 8,000 infantry, 30 guns and some 20,000 irregulars, many of them the religious fanatics known as Ghazis.

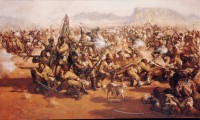

Battle of Maiwand in Afghanistan in 1880

After several hours desperate fighting the enemy had broken through to the rear of the British line and the 66th were fighting them on both sides. Colonel Galbraith, who was carrying the Queen’s Colour at this stage, rallied most of the survivors of his battalion in the watercourse, but the position was very exposed and he decided to retire to Khig, where use might be made of houses and garden walls. During the withdrawal Colonel Galbraith, still grasping the Colour, was killed.

About a hundred of the Regiment made their second stand in a walled garden. Surrounded by hordes of irregulars they fought on until only two officers and nine other ranks were left. This small group charged out of the garden, formed up back to back and continued to fire until the last of them fell.

The 66th received no official recognition for its services at Maiwand. No Victoria Crosses were awarded for the good reason that no one qualified to make recommendations had survived. It was a defeat, so no Battle Honour could be given for it. Nor, apparently, did it warrant a bar to the Afghan Medal. However, no one had anything but praise for the 66th. Even the Afghans, who valued courage above all other virtues, had been impressed, and one of their Colonels who had been present spoke in glowing terms of their admiration for the Regiment’s conduct. General Primrose, in his official despatch to the Commander-in-Chief, India, wrote:

". . . . history does not afford any grander or finer instance of gallantry and devotion to Queen and Country than that displayed by the 66th Regiment on the 27th July 1880."

The action appealed to the mood of nationalism which was prevalent in Victorian England at the time and inspired a poem to be written. A small white mongrel dog named "Bobbie", who was the pet of a Sergeant in the Regiment, was wounded in the battle but survived and became the Regiment's mascot. He was eventually brought back to England where he was presented to Queen Victoria at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. The Regiment’s Medical Officer, Surgeon Major A F Preston, who was wounded in the battle, was the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's character, Doctor Watson, who describes in A Study in Scarlet how he was shot while attending to a fallen soldier.

The loss of the Colours at Maiwand, coming soon after a similar loss at Isandhlwana in 1879, led to the end of the practice of carrying them into battle. In future they were to be left in safe keeping well away from danger.

In 1881 as part of the Cardwell reforms of the army the 49th and the 66th Regiments were amalgamated to become the 1st and 2nd battalions of the "Princess Charlotte of Wales’s (Berkshire) Regiment".

Further reading: Maiwand. The last stand of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment in Afghanistan, 1880 by Richard J Stacpoole-Ryding, available from the Museum Shop.